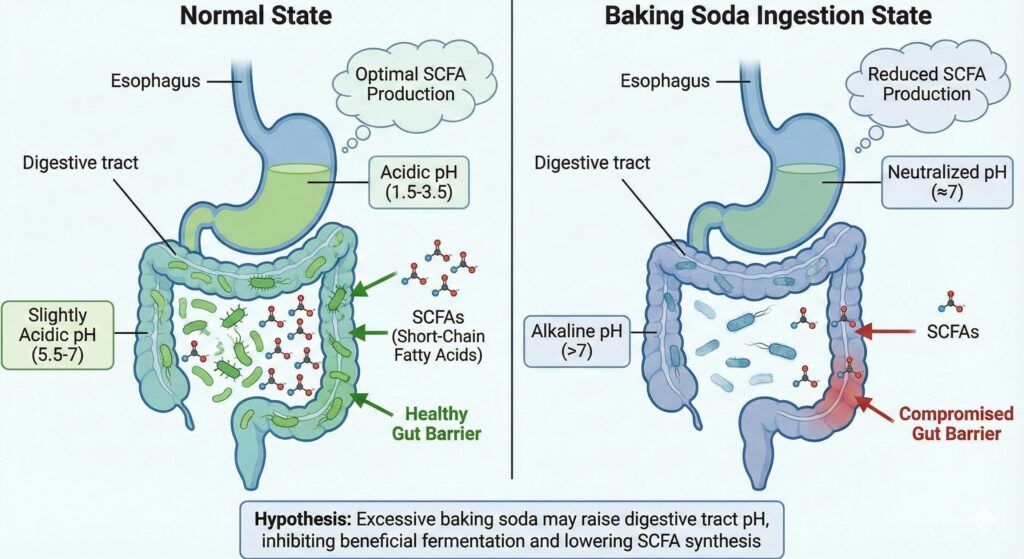

“Can taking baking soda cause a pH rise in the digestive tract and reduce SCFA production?”

The answer is yes, it is theoretically possible, but it depends heavily on frequency and dosage.

If pH (becoming more alkaline) in the wrong part of the gut, it can indeed inhibit Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) production. While baking soda is great for neutralizing stomach acid (heartburn), the bacteria in your colon actually require a slightly acidic environment to produce SCFAs like butyrate effectively.

The following breakdown details the mechanism behind this interaction:

1. The pH Gradient: How the Gut Should Work

Your digestive tract relies on specific pH zones to function. It is not a uniform tube; it is a series of chemical chambers.

- Stomach (pH 1.5 – 3.5): Highly acidic to sterilize food and digest protein.

- Small Intestine (pH 6 – 7.4): Bicarbonate from the pancreas naturally neutralizes stomach acid here so enzymes can work.

- Colon (pH 5.5 – 7): This is the critical zone for SCFAs.

- Proximal Colon (Start): Should be acidic (pH ~5.5) due to active fermentation.

- Distal Colon (End): Becomes closer to neutral (pH ~6.7) as SCFAs are absorbed.

2. The Mechanism: How Baking Soda Could Disrupt SCFAs

If you take baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) occasionally, your body handles it easily. However, if you take high doses (1 teaspoon or more at a setting) frequently (e.g., for “alkalizing” the body or chronic indigestion), two downstream effects can occur that risk SCFA production:

A. The “Downstream” Alkalinity Effect

While most baking soda reacts with stomach acid, high doses can overwhelm the stomach’s capacity, allowing excess bicarbonate to pass into the small intestine and potentially influence the pH of the chyme entering the colon.

- The Risk: Most butyrate-producing bacteria (like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia) act like “acidophiles” – they thrive in the slightly acidic environment (pH 5.5) created by their own fermentation.

- The Shift: If the colon environment becomes too alkaline (pH > 6.5 – 7.0), these beneficial bacteria slow down. It creates an environment that favors proteolytic bacteria (bacteria that rot protein) instead of fermentative bacteria (bacteria that ferment fiber). This shift halts SCFA production.

B. The Stomach Acid Trap (Hypochlorhydria)

Paradoxically, by neutralizing stomach acid too aggressively with baking soda, you may impair the “acid trigger” that tells the pancreas to release digestive enzymes.

- Without proper breakdown of food in the stomach, undigested proteins reach the colon.

- The fermentation of proteins (putrefaction) produces ammonia, which raises colonic pH (makes it more alkaline), further inhibiting the good bacteria that make SCFAs.

3. Is it Unhealthy?

Chronic use is likely unhealthy for the microbiome.

While baking soda is a cheap and effective tool for acute issues (like an occasional sour stomach or pre-workout buffering), relying on it daily could create a “feed-forward” loop:

- You take baking soda.

- Stomach pH rises (less acidic).

- Colon pH potentially drifts higher (less acidic).

- SCFA production drops (because butyrate producers go dormant).

- Since SCFAs (especially butyrate) are what keep the colon cells healthy and acidic, losing them causes the colon pH to rise further, perpetuating the cycle.

Summary

If you are trying to optimize SCFA production, you generally want to preserve the acidity of the proximal colon, not neutralize it.

Better Alternative for SCFA:

Instead of alkalizing the gut, focus on prebiotic fibers (like inulin, resistant starch, or acacia fiber). These fibers get fermented by bacteria, which naturally produces acids (SCFAs), lowering the colon pH to the healthy, acidic range where your microbiome thrives.

Taking baking soda can cause an unhealthy rise in pH across the digestive tract, which disrupts the specific environments needed for optimal gut health. While it serves as an effective antacid for the stomach, excessive or frequent use can push the colon’s pH from its naturally acidic state toward alkalinity, creating a hostile environment for beneficial bacteria. These microbes require a slightly acidic habitat to ferment fiber into Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which are essential for maintaining a strong gut barrier and regulating inflammation. By neutralizing this acidity, baking soda can inhibit SCFA production and lead to a compromised intestinal lining, highlighting the risk of using alkalizing agents that interfere with the gut’s delicate chemical balance.

Leave a Reply