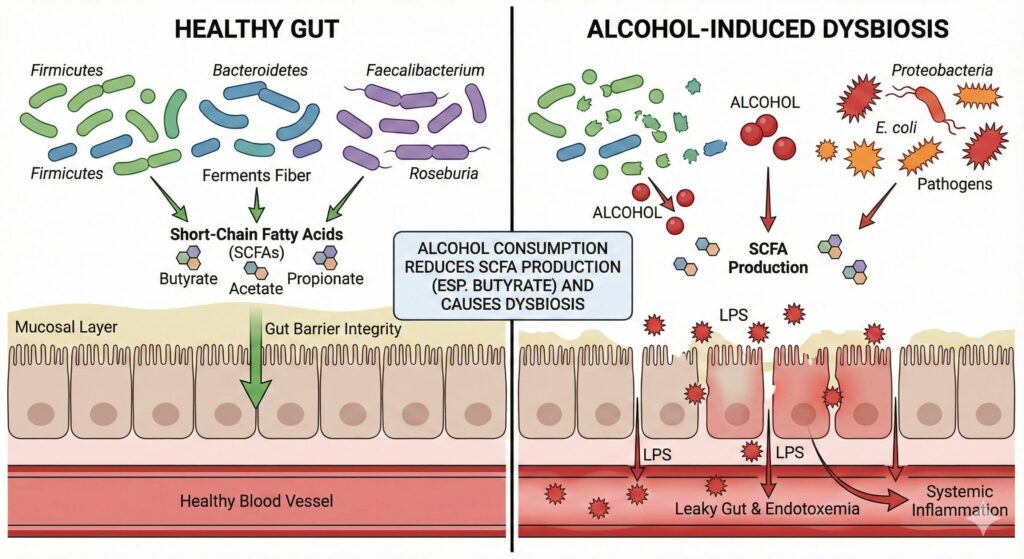

Yes, alcohol consumption is a well-established cause of gut dysbiosis and directly leads to a reduction in Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) production, particularly butyrate.

Research indicates that ethanol acts as a solvent and a toxin that disrupts the intestinal ecosystem, favoring pro-inflammatory pathogens over the commensal bacteria responsible for fermentation.

1. Mechanism of Alcohol-Induced Dysbiosis

Alcohol does not just “kill” bacteria indiscriminately; it creates a selective pressure that alters the composition of the microbiome.

- Reduction of Beneficial Families: Chronic alcohol consumption consistently suppresses members of the phyla Firmicutes (specifically the class Clostridia), which are the primary producers of butyrate. Specific genera often depleted include Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and Lachnospiraceae.

- Overgrowth of Pathogens: It facilitates the overgrowth of Proteobacteria (such as Escherichia coli) and Bacteroidetes. These gram-negative bacteria contain Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in their cell walls, which is a potent endotoxin.

2. Impact on SCFA Production

The reduction in SCFA levels is both a direct result of microbial shifts and a contributor to further damage.

- Butyrate Depletion: This is the most critical loss. Butyrate serves as the primary fuel source for colonocytes (colon cells). When alcohol reduces the population of butyrate-producing bacteria, the intestinal lining becomes “starved,” leading to weakened tight junctions.

- Acetate and Propionate: While alcohol metabolism in the liver actually produces acetate (leading to elevated systemic acetate levels), the gut-derived acetate and propionate produced by fiber fermentation are often disrupted due to the overall loss of bacterial diversity.

3. The “Leaky Gut” Cycle

The relationship between alcohol, dysbiosis, and SCFAs creates a self-reinforcing cycle of damage, often described via the Gut-Liver Axis:

- Lower SCFA availability: Without sufficient butyrate to fuel epithelial repair, the gut barrier weakens.

- Permeability: Alcohol directly damages epithelial cells and reduces the expression of tight junction proteins (like Zonula Occludens-1), causing “leaky gut.”

- Endotoxemia: The overgrowth of gram-negative bacteria increases the load of LPS (endotoxin). Because the gut barrier is leaky, this LPS translocates into the bloodstream.

- Systemic Inflammation: The liver receives this toxic, bacteria-laden blood via the portal vein, triggering inflammation (alcoholic liver disease) and affecting the brain (neuroinflammation).

Summary Table: Alcohol’s Effect on the Microbiome

| Component | Effect of Alcohol | Consequence |

| Diversity | Decreases | Reduced resilience against pathogens. |

| Lachnospiraceae | Decreases | Significant drop in butyrate production. |

| Proteobacteria | Increases | Higher production of toxic LPS (endotoxin). |

| Gut Permeability | Increases | Bacteria leak into the bloodstream (translocation). |

Recovery Note: The microbiome is resilient. Studies suggest that cessation of alcohol can allow SCFA-producing populations to rebound, often leading to a restoration of gut barrier integrity within “a few weeks of abstinence”.

Chronic alcohol consumption drives gut dysbiosis by significantly altering the microbiome’s composition, specifically suppressing beneficial, butyrate-producing bacteria (such as Firmicutes) while facilitating the overgrowth of inflammatory pathogens like Proteobacteria. This microbial shift leads to a critical reduction in Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) – particularly butyrate – which starves colon cells and weakens the intestinal barrier. Consequently, this loss of integrity creates a “leaky gut” that allows bacterial toxins (endotoxins like LPS) to translocate into the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation and liver damage via the gut-liver axis, a cycle that requires cessation of alcohol to reverse.

Leave a Reply