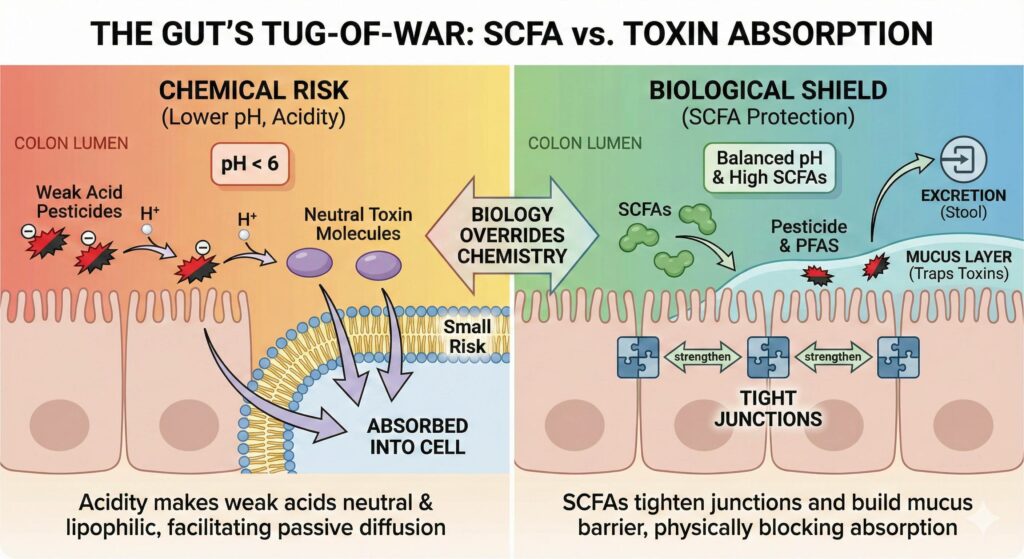

This is a complex biological question where the answer depends on whether you look at the chemistry of the toxins or the biology of the gut wall.

The short answer is: Physically, yes, but chemically, it might actually do the opposite.

While SCFAs (Short-Chain Fatty Acids) are incredibly protective, the acidity they produce (lowering the pH) can theoretically make certain pesticides easier to absorb. However, SCFAs counteract this by physically strengthening the gut lining to block those toxins.

Here is the detailed breakdown of this “tug-of-war” between chemistry and biology.

1. The Chemical Risk: Acidity Can Increase Absorption

Many common pesticides (like 2,4-D and Glyphosate) and some environmental toxins are classified chemically as weak acids.

- The Rule of Absorption: For a chemical to pass through the fatty wall of a cell (the cell membrane), it usually needs to be neutral (non-ionized). If it has a charge (ionized), it bounces off the fatty membrane.

- The Acid Effect: When you put a “weak acid” pesticide in an acidic environment (like a colon rich in SCFAs), the acidity forces the pesticide to hold onto its protons. This turns it into a neutral molecule.

- The Result: In a more acidic colon, weak acid pesticides become more “lipophilic” (fat-loving) and can theoretically drift across the gut wall easier than they would in a neutral or alkaline environment.

Note on PFAS: Most PFAS are “strong acids” with an extremely low pKa (often < 1). This means they stay negatively charged (ionized) even in an acidic colon. Therefore, the acidity produced by SCFAs likely does not significantly change their chemical absorption rate; they are absorbed through different active transport channels.

2. The Biological Shield: How SCFAs Stop the Absorption

If chemistry were the only factor, a healthy (acidic) gut might absorb more pesticide. However, biology overrides chemistry. The SCFAs (especially Butyrate) trigger biological mechanisms that physicaly lock the doors of the colon, preventing toxins from passing through the gaps between cells.

- Tight Junction Reinforcement:

The lining of your colon is made of cells standing shoulder-to-shoulder. The gaps between them are sealed by proteins called “Tight Junctions.” Toxins often slip through these gaps (paracellular transport). SCFAs signal your cells to produce more “glue” proteins (like ZO-1 and Occludin), tightening these seals and physically blocking large toxin molecules. - Mucin Production:

SCFAs stimulate the Goblet cells to produce more mucin (mucus). This creates a thick, physical barrier on top of the gut lining. Pesticides and PFAS can get trapped in this mucus layer and be excreted in stool rather than touching the gut wall. - Direct Binding:

The specific bacteria that produce SCFAs (like Bifidobacteria) can sometimes bind directly to toxins like PFAS and pesticides, holding them in the gut until they are pooped out.

Summary of the Mechanism

| Mechanism | Effect on Toxin Absorption | Why? |

| Lower pH (Acidity) | Increases (Risk) | Converts weak acid pesticides into a neutral form that slides through cell walls easier. |

| Tight Junctions | Decreases (Protective) | SCFAs tighten the seal between cells, preventing toxins from leaking through gaps. |

| Mucus Layer | Decreases (Protective) | SCFAs build a thicker mucus shield that traps toxins before they reach the cells. |

The Verdict

The acidic environment itself is not the shield; it is actually a potential liability for weak acid absorption. However, the SCFAs themselves are the shield.

The benefits of SCFAs (building a fortress-like gut barrier) vastly outweigh the small risk of increased chemical solubility. A “leaky gut” (low SCFA) will absorb far more toxins through the open gaps between cells than a healthy, acidic gut would absorb through chemical diffusion.

Leave a Reply